Golfing News & Blog Articles

Golf Ball Compression Guide

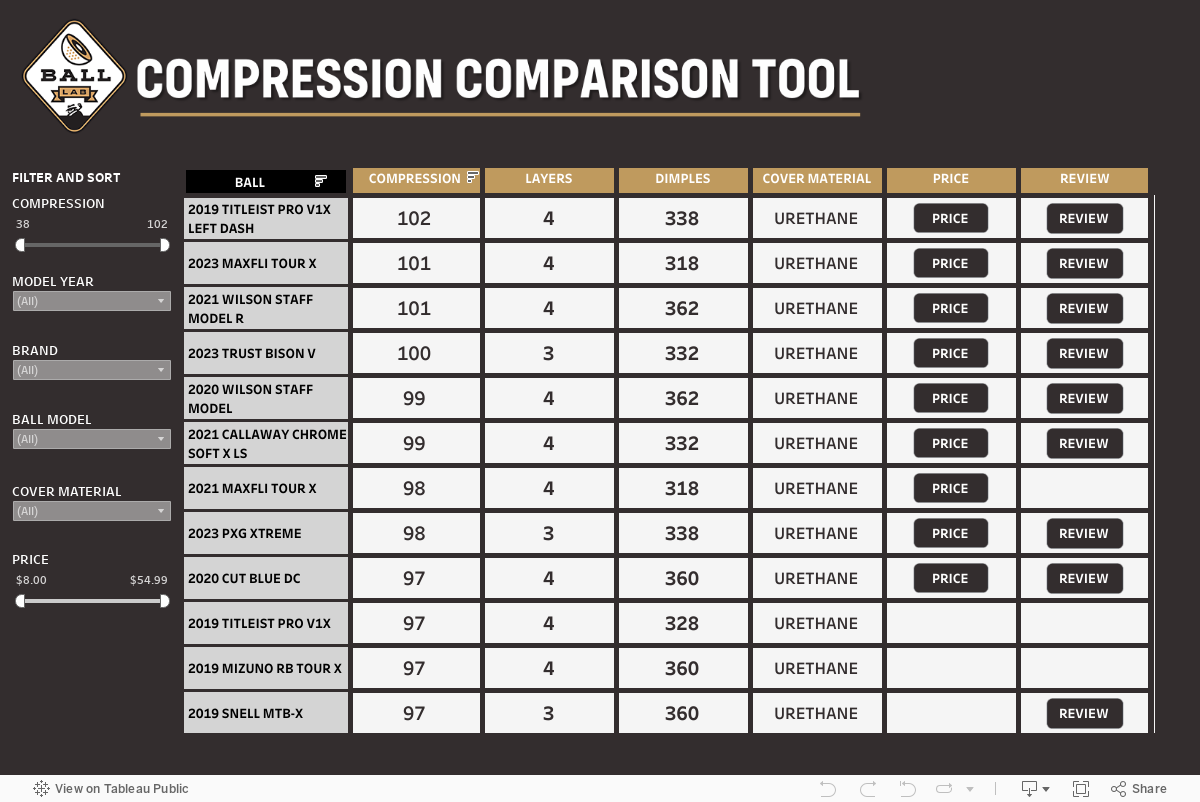

Where can I see golf ball compression numbers in one place?

That’s probably the most common question to come out of our work in the MyGolfSpy Ball Lab.

For golfers looking for that sort of thing, we’ve built a compression chart that includes every ball we’ve measured to date. In the interest of providing even more information, we’ve also included the layer count, number of dimples and cover material.

Below the chart, you’ll find a golf ball compression FAQ of sorts. The goal is to tackle your compression questions while hopefully clearing up what really is an abundance of golf ball compression misinformation found elsewhere.

As always, if you have more questions, drop them into the comment section.

Golf Ball Compression Chart

var divElement = document.getElementById('viz1653422177529'); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName('object')[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width='1200px';vizElement.style.height='827px';} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width='1200px';vizElement.style.height='827px';} else { vizElement.style.width='100%';vizElement.style.height='927px';} var scriptElement = document.createElement('script'); scriptElement.src = 'https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js'; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);Golf Ball Compression FAQ

Golf ball compression is a measure of how much a golf ball deforms under load. The higher the compression, the firmer the ball.

It should be noted that there isn’t a single industry-standard gauge and even gauges of the same type can produce slightly different measurements so it’s not uncommon for one manufacturer’s 90 to be another’s 85 or for our gauge to differ a bit from a manufacturer’s stated compression value.

By always using the same gauge, we’re able to create a uniform standard across all manufacturers and models.

Also worth a mention: Reported compression values are typically for the entire ball (that’s how we do it) though manufacturers will occasionally use a core compression number for marketing purposes.

Typically, higher-compression balls like the Titleist Pro V1x, Bridgestone Tour B X and Callaway Chrome Soft X will feel firmer. Lower-compression balls like the Callaway Supersoft, Wilson Duo and Srixon Soft Feel tend to feel softer.

Keep in mind that “feel” is a relative construct. A ball like the Bridgestone Tour B XS or Srixon Z-Star that’s considered soft by Tour standards is invariably firmer than urethane-cover balls marketed to moderate swing speed golfers (Chrome Soft, TOUR B RXS and even Titleist AVX). Those balls will be quite a bit firmer than two-piece ionomer offerings like the Pinnacle Soft, Wilson DUO or Callaway Supersoft.

Generally speaking, at similar compression, a ball with a urethane cover will feel softer than an ionomer-covered ball. As an example, on our gauges, the Titleist Velocity is only two compression points firmer than the AVX. However, I’d wager most golfers would describe the AVX as significantly softer.

A final note on feel: Manufacturers aren’t always to be trusted in how they describe the feel properties of their golf balls. It’s not uncommon for 90-plus compression balls to be marketed as offering “soft feel” (they don’t) and while Chrome Soft X and Chrome Soft X LS have “Soft” in their names, they’re among the firmest balls on the market.

As we discovered in our first robot ball test, “soft” is slow. That is to say that lower-compression balls are slower off the driver. For higher swing speed golfers, the speed loss can translate to a significant loss of distance.

For slow to moderate swing speed players, soft balls are still slower but those percentage differences translate to minimal distance loss. At swing speeds in the low 80s and below, it’s probably not worth worrying about.

As you move into mid and short iron shots, the outer layers of the golf ball (mantle) play a larger role in the speed equation. In many cases, low-compression golf balls are longer off the irons.

There isn’t an absolute correlation between compression and spin but the nature of low-compression golf balls limits how much spin can be designed into the ball.

The thing to understand is that spin is the result of stacking a soft layer over a hard layer. When low compression and soft feel are the goals, the layers need to be softer than they are in high-compression golf balls.

That soft-over-soft relationship ultimately means low-compression (i.e., “soft”) balls are typically lower-spinning than firmer ones. It is possible to make a lower-spinning firm ball but, as a rule, the softest balls tend to be the lowest spinning.

That’s neither good nor bad but it is a bit of a double-edged sword. Lower driver spin can mean straighter flight while low iron spin can make it more difficult to hold greens.

A golf ball’s trajectory is driven almost entirely by its dimple pattern and it’s theoretically possible to put any dimple pattern on any ball.

In that respect, compression has no impact on flight.

That said, while there are exceptions (Titleist AVX is a relatively low-flying ball by low-compression standards), most low-compression golf balls are paired with high-trajectory dimple patterns. The idea is to offset the loss of spin with a higher flight and softer landing angles.

The short answer is no. The softest golf balls on the market pair a firmer ionomer cover with a soft core. As noted, spin is the product of a soft layer over a firm one. Soft over firm spins. Firm over soft doesn’t. You might have been told differently but the reality is that balls like Super Soft, Soft Feel and DUO are invariably going to spin less around the green than a Pro V1, Tour B XS or Z-Star.

The urethane cover is going to be the softest layer of the ball while the underlying mantle layer is typically the firmest so if greenside spin is important, a multi-layer ball with a urethane cover is non-negotiable.

Keep in mind that not all urethane covers are equally soft and not all mantle layers are equally firm. The balls with the greatest separation between cover and mantle firmness should be the ones that spin the most around the green.

The idea that there is a right compression for your swing speed is likely the most pervasive myth in the ball-fitting world and it has almost no basis in fact.

At swing speeds as low as 60 mph, you’re compressing the core of the golf ball. The performance risk isn’t from slower swingers under-compressing the core of a firmer ball, it’s from faster swingers over-compressing the core of a softer one.

And even then, there aren’t any absolutes. While most faster swingers should probably avoid lower-compression balls, for some higher swing speed, high-spin players, the speed loss can be offset by the lower spin properties.

It’s the reason why, when it comes to ball fitting, your focus should be on trajectory and spin.

It may surprise you to learn that Titleist fits more amateur golfers into Pro V1x than any other ball in its lineup. It’s a reality that defies much of what’s been published elsewhere but the fact is that many golfers—especially lower to moderate swing speed golfers—benefit from the higher flight and spin characteristics of the ball.

Likewise, while Chrome Soft is the most popular ball in Callaway’s urethane lineup, I’d wager a significant number of average golfers would benefit from the higher spin properties of the Chrome Soft X.

More questions?

Have more compression questions? Drop them in a comment below and we’ll try and answer them in a future #AskMyGolfSpy.

The post Golf Ball Compression Guide appeared first on MyGolfSpy.