Golfing News & Blog Articles

History’s Mysteries: The Ram Golf Story

Welcome back, my fellow time-traveling GolfSpy, to a long overdue dive into History’s Mysteries.

Let’s pop some crystals into Uncle Rico’s Time Machine Modulus and place the Tee Handle in accordance with the user’s manual. Throw the switch, Kip, our mission is to go back in time and examine the birth, life, death and rebirth of Ram Golf.

Ram never reached the heights of Wilson, MacGregor or Hogan, but the company had more firsts to its credit than you might realize. In its heyday, Ram had more than 50 PGA TOUR and LPGA Tour pros in its stable, headlined by Tom Watson.

And the crazy thing is that Ram started as a family business that got into golf almost entirely by accident.

History’s Mysteries: The Strange Story of Ram Golf

Before Carlsbad became golf’s equipment mecca, there was Chicago. It was home to some of the biggest companies in golf back in the day. There was Wilson Staff, of course, along with Northwestern and Lamkin. PGA Golf, which eventually became Tommy Armour, was in Morton Grove.

But it was the post-WWII manufacturing boom that drew Lyle Hansberger and, eventually, his three younger brothers to town.

Lyle, Bob, Al and Jim Hansberger, by nature and necessity, were drawn to engineering. Raised on a dairy farm in Worthington, Minn., the Hansberger brothers learned how to fix everything themselves. And their parents, Floyd and Edith, made sure they pursued an education.

Lyle earned his engineering degree from the Dunwoody Institute in Minneapolis. After working for IBM during the war, he decided to put his degree to work in Chicago. With his $500 life savings, Lyle opened the Hansberger Tool and Die Company at 101 George Street.

Getting Started

As you’d expect, club manufacturing in the U.S. stopped during WWII. Once the war was over, however, pent-up demand caused a run on golf equipment. Manufacturers found themselves scrambling for machinery and capacity.

And Lyle Hansberger was the right guy in the right place at the right time with the right stuff.

Lyle contracted with both Northwestern and a smaller Chicago company owned by George MacGregor (no connection to the larger, better-known MacGregor Golf Company), to make dies and club-making equipment. He also started a night shift to help MacGregor with stamping, grinding and assembly. Soon brothers Bob, fresh out of Harvard Business School, and Al arrived to help out.

Immediate Success

By 1948, the Hansbergers’ golf business was booming. They pooled $5,000 and bought MacGregor’s company lock, stock and 5-iron. They renamed their new company Sportsman’s Golf with the goal of making affordable golf equipment for the working man.

Sportsman’s was an immediate success, making as many as 10,000 clubs a day. However, the company had no warehouse. So, at the end of each day, all the product would be loaded into a truck and covered with a tarp. The older brothers would then hand the youngest brother, Jim, a gun, telling him to guard the inventory with his life.

By 1950, the company moved to larger digs at 1300 Hubbard Street in Chicago. By 1952, Sportsman’s hit the $1-million mark in sales. Never ones to sit still, the Hansberger brothers went into acquisition mode, purchasing the Bristol and Kroydon golf brands at relative bargains.

While Sportsman’s remained the affordable retail brand, Bristol and Kroydon put the Hansbergers squarely into the pro-line game.

This new multi-channel, multi-brand approach worked well, prompting the company to move once again to a much larger facility in Melrose Park. By the late ‘50s, the Hansbergers contracted with George Low to manufacture Low’s legendary Wizard 600 putter under the Sportsman, Bristol and Kroydon names. Jack Nicklaus won 15 of his 18 majors with a Wizard in his bag.

The Swingin’ ‘60s and the Birth of Ram

Sportsman-Bristol-Kroydon rode a wave of profits into the new decade. The company had been making balls using the Ram name at a ball plant in Bay City, Mich. But In 1964 the Hansbergers decided to buy the plant outright. And with it came the services of a research chemist named Terry Pocklington.

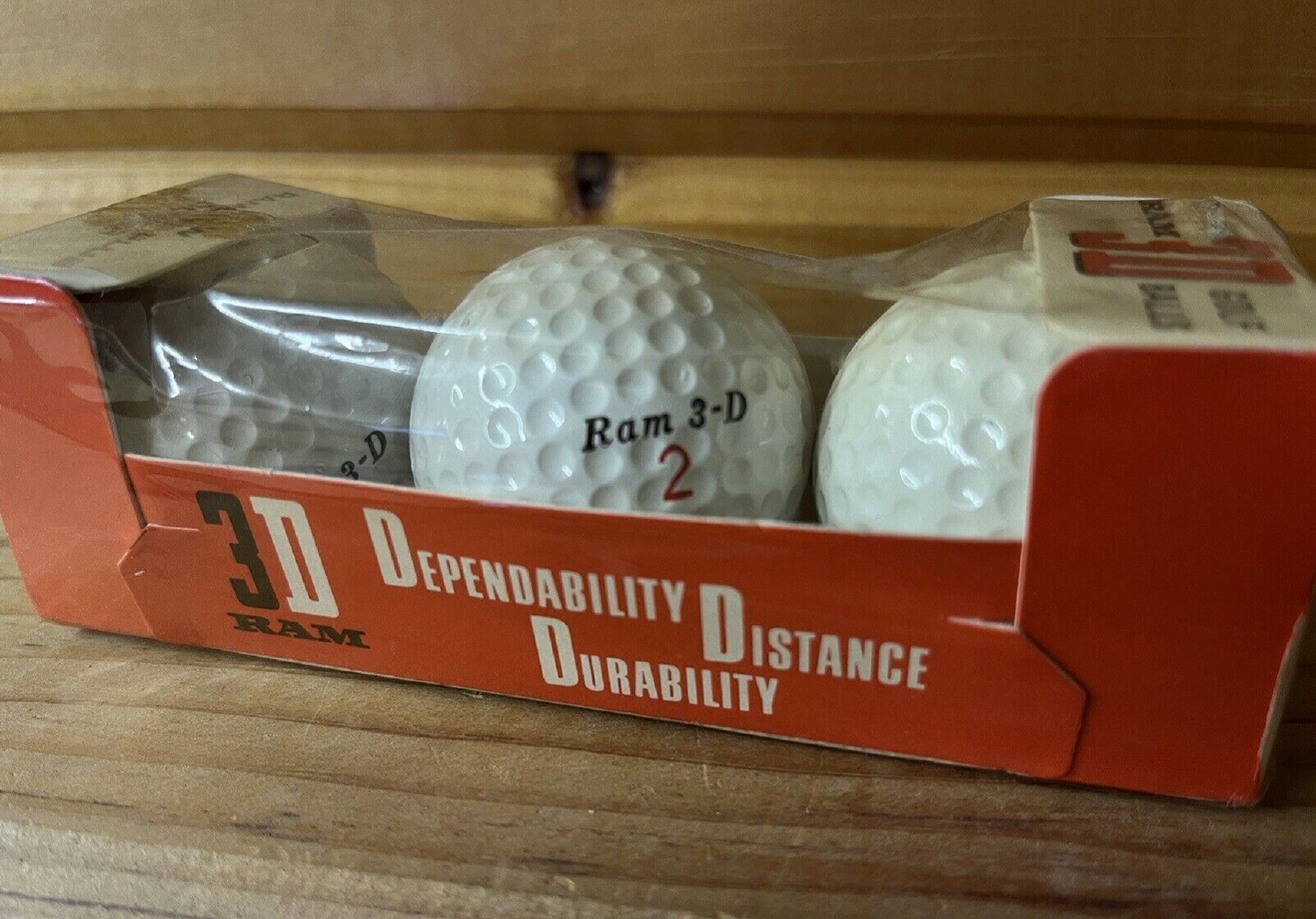

You may not know the name but Terry Pocklington is regarded as the father of the Surlyn-covered golf ball. The Hansbergers moved the Bay City plant south to Mississippi, with Lyle moving with it to head up R&D. And it was in Mississippi that Pocklington developed and patented the Ram 3-D, the game’s first commercially marketed Surlyn ball. The cover carried the tradename Ramlon.

Anyone who’s ever played a balata knows it would cut if you just look at it crossly. The new Ram 3-D gave golfers no-cut distance priced for the masses.

The new ball turbocharged growth and by 1967 the Hansbergers rebranded the company under one name: the Ram Golf Corporation. The Sportsman and Bristol names were retired. Kroydon remained as the company’s retail line, with clubs named for Tour pros Tommy Bolt, Doug Sanders, Gene Littler and Jo Ann Prentice. Kroydon was mothballed in 1970, and everything was sold under the Ram brand name.

Ram rode Ram 3-D for all it was worth, retaining exclusive rights until 1970 when Spalding introduced its version, the Top-Flite.

Toothpaste, Mouthwash and Dishwashing Liquid

As often happens in family businesses, the Hansbergers reached a skill-set limit. Excellent engineers with a strong commitment to their customers, the brothers lacked the resources and know-how to take the company any further. Additionally, they’d reached middle age and all their money was tied up in the company.

Conditions were ripe for a sale. What they needed was a deep-pocketed, golf-obsessed buyer to write them a really big check.

Enter Colgate-Palmolive.

A $2-billion global company, Colgate-Palmolive had deep pockets. And Chairman David Foster was most definitely golf-obsessed. Foster’s plan was to use sports, specifically women’s golf, to sell more toothpaste, mouthwash, dishwashing liquid and laundry detergent. He had already purchased Penfold in the UK, and in 1974 he bought out the Hansbergers for $20-million worth of Colgate stock.

Lyle, Al and Jim Hansberger stayed on, but with short-term deals. Al and Jim eventually left to start their own golf club components company but Lyle stayed to run the Mississippi ball plant.

Colgate-Palmolive spent $3 million to $4 million annually on promotion, almost entirely on Tour staff. Tom Watson signed on to Ram during that time as did Ray Floyd, Calvin Peete, Nancy Lopez and more than 50 others, including a young Seve Ballesteros and Nick Faldo in Europe. Colgate-Palmolive also spent big dollars to sponsor major tournaments, most notably the Penfold PGA Tournament in the UK and the Dinah Shore LPGA major in Palm Springs.

Colgate-Palmolive’s mid-70s marketing was changing. It still targeted the traditional “housewife” market (remember Madge, the manicurist?). But Foster wanted to use golf to target modern, active women who still did the laundry, washed the dishes and did the shopping.

Colgate-Palmolive: Synergy or a Bad Fit?

In theory, a conglomerate whose primary business is oral hygiene and clean dishes is a curious fit with a golf company. In reality, there was nothing curious about it. It was a terrible fit. Ram, like its British cousin Penfold, was a small family business. Colgate-Palmolive wasn’t. The new ownership brought in waves of its own people with no golf experience whatsoever, which led to endless meetings.

In a May 1990 article by Dan Rottenberg in Family Business Magazine, Jim Harnsberger said the corporate office would send out department head after department head. “We were so busy meeting them or lunching them or flying to England with them that we didn’t have time to run our business.”

Prior to the sale, Al and Jim would spend 30 to 40 percent of their time dealing directly with customers. After the sale that dropped to about five percent. In addition, Rottenberg writes that Colgate executives under Foster never really bought into the Ram-Penfold venture, considering it Foster’s “personal ego trip.”

The Colgate-Palmolive years weren’t all bad for Ram. As mentioned, the Tour staff was substantial, and Ram acquired the right to make and market the distinctive-looking Zebra putter in 1975. Ram got a huge boost a year later when Ray Floyd set the 72-hole scoring record at the Masters with a Zebra.

Despite the successes, Ram and Penfold remained small dots on the Colgate-Palmolive org chart. The Hansbergers never had any personal issues with the new management, but the company cultures never meshed. What’s more, Foster’s hoped-for synergy to sell more toothpaste failed to move the needle. And when Foster retired in 1979, Colgate-Palmolive couldn’t get out of the golf business fast enough.

Back Home Again

When you discuss Deals of The Century, the Hansbergers’ repurchase of Ram in 1979 has to be near the top of that list. Al, Jim and Lyle had great relationships with the Colgate-Palmolive team. Whether that relationship helped them get such a sweetheart deal is unknown but the brothers were able to buy Ram back for considerably less than the $20 million they had sold it for just five years earlier.

“The company we reacquired from Colgate was quite a different company from the one we sold,” Jim is quoted in Rottenberg’s article as saying. “The best business education we ever had came during that Colgate period.”

Jim took over as CEO. He immediately cut Ram’s Tour staff to the bone, retaining only Watson and a handful of others. Additionally, Ram had been selling Zebra putters as a licensee. But in 1980, the company bought Zebra outright.

Jim also refocused Ram on pro-line equipment. In 1982, it launched the first commercially successful line of frequency-matched clubs, featuring Joe Braly’s Precision shaft.

Ram spent the ‘80s focusing on its custom club-fitting and club-making service. At one time, it was ranked by Golf Magazine as the No. 1 custom club maker in the business. Ram also expanded into sportswear and in 1987 acquired Country Club Systems, a software company that created accounting and operating systems for private country clubs.

Ram and The Roaring ‘90s

By any reasonable measure, the ‘90s was golf’s most dynamic decade. It started with Faldo winning the Masters and Callaway selling $5-million worth of Big Berthas. It ended with Tiger winning the first leg of the Tiger Slam and Callaway sales approaching $1 billion. The old guard of Wilson, MacGregor and Spalding, however, were sliding toward irrelevance.

Ram was stuck in the middle, but there was ominous writing on the wall.

“Ram survived its first 50 years by making high-quality products that make the game easier and more enjoyable,” Marketing VP Jerry Fortis told the Chicago Tribute in July 1997. “To make whiz-bang, high-techie products would be inconsistent with our image.”

Unfortunately, whiz-bang, high-techie products were what was selling.

By 1996, a crazy decade was about to get a whole lot crazier. That year alone, Acushnet bought COBRA for $700 million, Zurn sold a struggling Lynx to an all-star investment group (it went bankrupt in ’98) and Spalding was sold to KKR for an astounding $1 billion.

In 1997, Spalding acquired Ben Hogan, Callaway bought Odyssey and adidas bought TaylorMade. Golf was becoming a big business. It’s the very definition of irony that the July article on Ram in the Chicago Tribune was titled “Small is Beautiful.”

Small may be beautiful but, for Ram, it was no longer sustainable. Within five months of that story, the Hansbergers would cash out one last time.

Slucker Steps In

Rudy Slucker made so much money in the hardware business that he retired by age 40. In 1996, he bought the struggling Teardrop Putter company because, in his words, “I needed something to do.”

Slucker turned Teardrop around, selling $800,000 worth of putters in his first year. Then he got cocky. In November of ’97, Slucker purchased Tommy Armour, which hadn’t turned a profit in years, for $25 million. A month later, he bought the Ram Golf Club Company for the bargain basement price of $10 million in cash and stock (Ram’s golf ball business had been sold to TaylorMade two years earlier).

Slucker certainly didn’t lack confidence. Golf writer Ron Sirak quoted Slucker as saying, “The question is: ‘Do I buy NIKE or does NIKE buy me?’” He repositioned Ram as a low-priced line for sporting goods stores and discounters. But his magic touch had vanished. Deeply leveraged, loaded with debt and staring into an abyss of red ink, Teardrop filed for bankruptcy in December 2000.

Ram and its stablemates would change hands three more times over the next four years, eventually landing with Huffy, the bicycle company. Huffy filed for bankruptcy a few months later and Sports Authority scooped up its assets. Ram became Sports Authority’s ultra-cheap store brand. And it became a non-entity when DICK’s bought Sports Authority’s assets out of bankruptcy in July 2016.

History’s Mysteries: The Rebirth of Ram

Thanks to the Sports Authority bankruptcy, DICK’s now owned the Ram, Zebra, Teardrop and Tommy Armour brands. Within weeks, DICK’s added the MacGregor and Lynx names when GolfSmith went belly up. DICK’s kept Tommy Armour as its house brand but sold Lynx off to a couple from England, who relaunched the brand in the UK.

Eventually, DICK’s sold the Ram, Zebra, Teardrop and MacGregor names to entrepreneur Simon Millington and his company, Golf Brands, Inc. Millington released new MacGregor clubs this past January as well as an updated line of Zebra putters. And he’s reintroducing Ram as a performance/value line.

Millington showed the new Ram FX77 irons at this year’s PGA Show. The FX77 is a hollow-body, foam-filled iron that straddles the game improvement/player’s distance categories. And it’s priced to move at $399 for a seven-piece set in chrome ($449 in black). Millington is upfront in saying the irons are an open model. They do bear an uncanny resemblance to Sub 70’s previous generation 699 irons but Sub 70’s Jason Hilland still owns those molds. That’s not to say another factory in China hasn’t borrowed the design, a strategy not uncommon over there.

We’ve demoed the new Ram FX77 irons and the early returns are extremely positive. We’ll know more once we get them on the course but at $400 they appear to be a hell of a bargain.

The Hansberger Legacy

Despite making some outstanding equipment and its longstanding relationship with Tom Watson, Ram never was a real force in golf.

Its legacy, instead, lies with the Hansberger brothers. Before researching this article, I knew them only by name. But the Hansbergers made Ram the rare family business where the sum of the parts worked to create a greater whole.

Oldest brother Bob was the family businessman. Bob never did work directly with his brothers at Ram. He was too busy in Idaho putting together the $8-billion lumber giant Boise Cascade. After retiring in 1972, Bob served on several Presidential Commissions and on the boards of more than 15 major corporations, including ABC, General Dynamics and Manufacturers Hanover Trust. He passed away in 2008.

Lyle, the engineer-brother who started it all, moved to Mississippi in 1965 to run the ball and R&D plant. He never left. After Ram, he served as a U.S. trade ambassador and on various boards at Mississippi State University. Lyle died in 2009.

Al was the salesman of the family. His post-Ram work included the Campaign for Equal Justice and the Boys and Girls Clubs. In 2018, on behalf of the family, he donated $1 million to the Kids Golf Foundation of Illinois which has introduced more than 250,000 young people to the game. Al died last October at the age of 98.

Jim, the youngest Hansberger, was said to have been a combination of his three older brothers. He served as Chairman of Ram from 1979 through the sale in 1997. He passed away just this past January at the age of 88.

History’s Mysteries: The Ram Epitaph

In Dan Rottenberg’s Family Business Magazine article, Jim perhaps summed up the Ram-Hansgerger story best:

“We’re in this business for the relationships and the accomplishments, as opposed to a sheerly financial approach. The financial approach is important, but it’s not the dominant emphasis for this family.”

Looking back on the changing golf climate of the ‘90s, and where the industry has gone since, it’s a good thing the Hansbergers cashed out when they did. Ram would never have survived in the new world order. These were smart guys. They had to have seen what was coming.

Golf’s transformation to “Big Business” started in the ’90s and is now complete. Both Acushnet and Topgolf-Callaway are multi-billion-dollar behemoths while the family touch that made the Hansbergers successful is largely gone. But you can find it if you look hard enough. Millington, for example, is building MacGregor-Ram-Zebra-Teardrop with his two sons. You could fly coach from Detroit to Chicago and find yourself sitting next to Tour Edge founder David Glod. And one of the attractions of DTC companies such as Sub 70 or New Level is the personal touch of owners Jason Hilland and Eric Burch.

It’s an oversimplification to say corporate business is all about top-line sales and bottom-line ink. The good ones do have a soul. Family businesses are about the dollars as well but, to use Jim Hansberger’s words, they’re also about relationships and accomplishments. To corporate bean counters, an iron set, driver or lob wedge may just be SKUs and numbers on the bottom of a ledger. But they’re also the tools you use every weekend to play a game you love.

The Hansberger brothers understood and respected that. And that’s what makes Ram worth remembering.

The post History’s Mysteries: The Ram Golf Story appeared first on MyGolfSpy.